blog post

The Cyber Caremark Lawsuit: A Cautionary Tale

Back in 2015, after months of speculation, a shareholder stepped up and filed a derivative lawsuit against the directors and management of The Home Depot, Inc., in connection with the massive data breach the company suffered in 2014. The complaint, which alleges breach of fiduciary duty and corporate waste, fits the emerging template of shareholder derivative lawsuits after breaches at public companies.

As such, it is worth a closer analysis for those whose jobs include protection of public companies and their boards from and during data breaches, both directly through more robust cybersecurity measures and indirectly through director and officer insurance and cyber-risk policies.

The Complaint

The derivative complaint was filed in August 2015 in federal court in Atlanta and was unsealed in early September. It blames the 12 individual defendants — 11 current and former directors and officers at Home Depot, as well as the company’s general counsel — for failure to oversee the company’s cybersecurity adequately. This failure allegedly resulted in the breach in which hackers spent months accessing the company’s networks and stealing the personal and financial information of approximately 56 million customers. According to the complaint, the breach harmed the company by exposing it to dozens of lawsuits, additional regulatory investigations, and millions upon millions in attendant fees and costs.

The plaintiff asserts that the defendants’ failure to oversee the company’s cybersecurity constituted a breach of their fiduciary duties, particularly the duties of loyalty and good faith. In that regard, the plaintiff — like the shareholders who filed derivative actions following the Target data breach — is pursuing what we have dubbed a “cyber Caremark” lawsuit. In re Caremark International Inc. Derivative Litigation, 698 A.2d 959 (Del. Ch. 1996), first outlined the basis of a derivative claim grounded in inadequate oversight. While Caremark had nothing to do with cybersecurity, it is clear that plaintiffs are now grafting that theory of liability onto data breaches. While a Caremark claim presents a high burden for a plaintiff, this is still bad news for corporate boards. Detailed Caremark claims are costly to litigate. And state corporate law (such as that of Delaware, which applies to Home Depot) limits the extent that a company can insulate and indemnify its directors from monetary damages for breaches of the duties of loyalty and good faith.

Indeed, we expect derivative lawsuits to become much more common following data breaches at public companies. While the plaintiffs’ bar has had some recent successes bringing large consumer class actions after data breaches, those suits have not always succeeded, given — among other hurdles — issues of standing and causation. Many of these impediments are not present with derivative litigation, which generally requires a single shareholder to make a demand on the board (or plead demand futility) and then file suit.

Outside the cyber context, derivative demands often trail consumer litigation (in the products arena) and regulatory action (in the securities fraud context). Cyber will be no different. That is, plaintiffs’ attorneys drafting demand letters and derivative complaints can borrow from the work of others, translating related claims into the language of corporate mismanagement. Additionally, because derivative cases are costly to investigate and defend, they often result in relatively quick settlements. Add to that the fact that successful derivative plaintiffs often can recover their fees under applicable state statutes, and you have a perfect storm for a rise in derivative litigation after a data breach.

Before the Breach

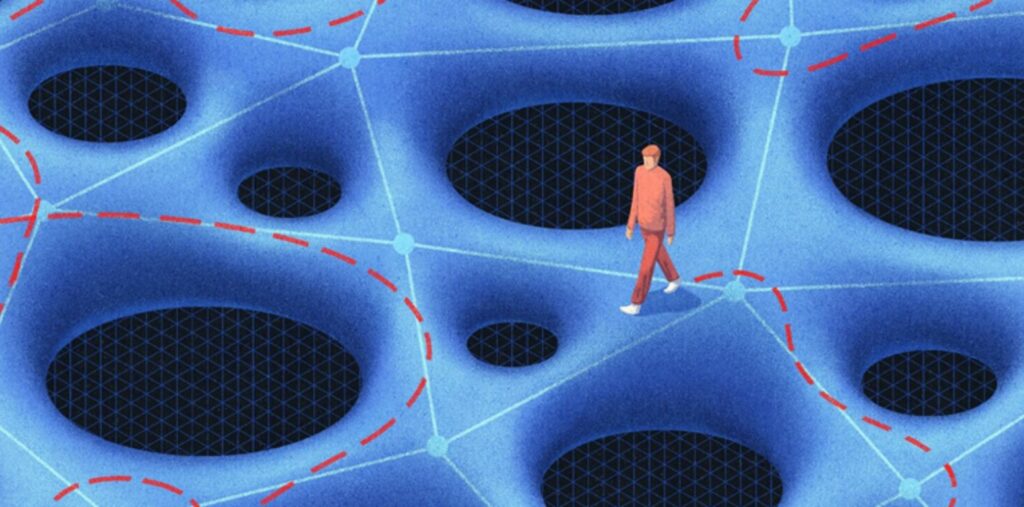

Armed with the understanding that these claims are a locomotive barreling towards them, directors, officers, and those who advise them must take action now. By laying the right tracks, these stakeholders will be able to manage data breaches — and the ensuing litigation — like any other major risk to their companies.

Liability for directors and officers in a cyber Caremark derivative action will likely depend on whether those individuals put in place before the breach a reasonable process calibrated to the company’s data, risk profile, and regulatory environment. And the expense of the defense will be directly proportional to how well this preparation was documented. In this regard, the following proactive best practices should be considered:

Conduct a risk assessment that evaluates the nature of the company’s data, its vulnerability to hackers, and the ramifications if it were compromised.

Draft policies and procedures, as well as an incident response plan, that not only seek to prevent a data breach but also outline the steps to take after such an event occurs.

Consider whether the company’s existing insurance policies provide the requisite coverage for data breaches, as well as defense of the directors and officers in the event of litigation post-breach raising a Caremark or other derivative claim.

Evaluate the “tech IQ” of the company’s directors and officers, and then task (or hire) a director to take the lead on cybersecurity oversight, serving as a liaison between the directors and management’s head of IT security. Provide regular updates to the board regarding cybersecurity and use third-party consultants as appropriate.

Work with counsel to review and update the company’s public disclosures related to cybersecurity. This is a critical issue, given the SEC’s increasing focus on cybersecurity disclosures. And, plaintiffs — including the Home Depot derivative plaintiff — are likely to use the company’s cybersecurity disclosures to their advantage in litigation (e.g., to argue that the company overstated its defenses).

Boards and company executives can no longer profess ignorance about their company’s cybersecurity. The Home Depot derivative complaint takes the defendants to task for allegedly failing to ensure that the company encrypted customer data, used up-to-date firewalls and antivirus software, and monitored network access. The granularity of the allegations would have been shocking even five years ago, but is far less so today. In other words, the blame for these failures is no longer confined to a company’s IT department.

After the Breach

Just as directors’ and officers’ conduct pre-breach is coming under scrutiny, so too is their conduct post-breach. Shareholder plaintiffs, following the Home Depot plaintiff, should be expected to criticize them for failing to detect and respond properly to the incident. Accordingly, after a data breach, the directors and officers must consider these items to minimize damage to the company and personal liability:

Activate the incident response plan, and then evaluate, depending on the size and nature of the event, the extent to which the board should be notified and kept apprised of developments.

For a major incident, involve the board early and often through formal, telephonic meetings and informal briefings of the lead cyber director. Consider giving the board access to the outside investigators and counsel involved in breach clean-up.

Depending on a variety of factors, including the size of the breach and the industry in which the company operates, consider reaching out to law enforcement and regulators, briefing the board on the results.

For both the company’s prophylactic measures and post-breach actions, it is critical that the attention to cybersecurity be documented. This includes keeping and retaining board minutes, briefing books, and other records of activity so that the directors and officers can “show their work” when their conduct becomes the subject of litigation and investigations. That important step — when combined with the items above — should help to mitigate exposure for directors and C-suite executives, who will increasingly find themselves in the uncomfortable position of their counterparts at Home Depot.

Author

Steve King

Managing Director, CyberEd

King, an experienced cybersecurity professional, has served in senior leadership roles in technology development for the past 20 years. He has founded nine startups, including Endymion Systems and seeCommerce. He has held leadership roles in marketing and product development, operating as CEO, CTO and CISO for several startups, including Netswitch Technology Management. He also served as CIO for Memorex and was the co-founder of the Cambridge Systems Group.